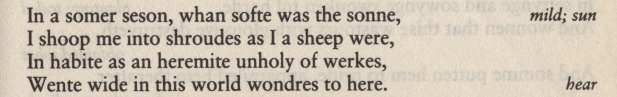

As you can see from your copy of Piers Plowman (or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, or whatever), modern scholarly editions of alliterative verse usually present each line as an unbroken unit:

However, each line can actually be divided into two halves:

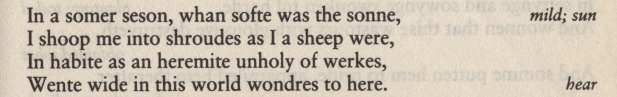

So, taking the opening of Piers, hopefully it's easy to see (and hear) where the break falls. Hover on the following lines where you think the caesura should be; unless you have an evil, incompetent browser, it should tell you when you get it right!

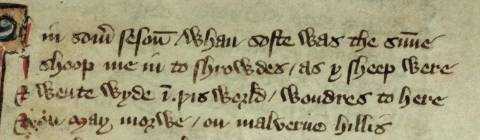

Medieval scribes were actually more helpful to their readers in this respect than modern editors. Have a close look at the following image, for example: it's MS Oxford, Corpus Christi College, 201, f.1r, with a slash between each a-verse and b-verse.

So don't be afraid to annotate your copy of Piers--you'll be in good company!

The first heavily stressed syllable in the a-verse must alliterate with the first heavily stressed syllable in the b-verse. Easy!

Most students are a bit confused about what stress is and how to identify it. (So if you don't understand this section, click here for more help!) Alliterative verse is only concerned with the most heavily stressed syllables in a line. Fortunately, the stress rules of alliterative verse are basically the same as normal speech today--so you just have to listen for what's heavily stressed when you read the text out like normal prose. But people are often unused to thinking of poetry this way, because post-medieval poetry doesn't tend to work this way.

Poets like Chaucer or Shakespeare were only interested in whether a syllable is more or less heavily stressed than its neighbours, so when we listen to their poetry, we're generally expecting an alternation of 'stressed' and 'unstressed' syllables. But the reality is that there are several different levels of stress in English. Alliterative poets were generally only interested in the most heavily stressed syllables. So when Shakespeare wrote

But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?he was thinking of the singy-songy rhythms characteristic of iambic pentameter:

It is the East and Juliet is the sun

But soft, | what light | through yon | der win | dow breaks?But if we say these lines like normal people (insofar as normal people ever say things like 'but soft' and 'yonder window'), only the following syllables would be heavily stressed:

It is | the East | and Ju | liet | is the sun.

But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?It's these heavy stresses that alliterative poets care about.

It is the East and Juliet is the sun.

So for people used to the poetry of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and their ilk, it's tempting to try to read things like Piers Plowman as a sort of unholy mixture of Shakespeare-style iambs and trochees:

In a somer seson, whan softe was the sonne,But we should actually read it out like normal prose, and let the heavy stresses stand out:

I shoop me into shroudes as I a sheep were.

In a somer seson, whan softe was the sonne, I shoop me into shroudes as I a sheep were.

For more help with spotting heavily stressed syllables, click here.

When you're learning to look for stressed syllables, it's often easiest to work backwards from the end of the line, because the end is usually more regular than the beginning. So try hovering on the last heavily stressed syllable--remember, this is almost always the second to last syllable. Try hovering on the last stressed syllable.

Since the b-verse only has one other heavily stressed syllable, it should now be pretty obvious which it is--have a hover!

Now we know the alliterating sound of each line: respectively, s, sh, h, and w. SO the first stressed syllable of the a-verse will start with corresponding sounds. Try hovering on the first stressed syllable of each a-verse:

Like it says: any vowel can alliterate with any other vowel, as in 'And sithen in the eyr on heigh | an aungel of hevene'.

(This is probably because in clearly articulated English, we unconsciously add in a glottal stop before vowels, so its actually this unwritten consonant that is alliterating.).

So the first heavily stressed syllable in the first half has to alliterate with the first heavily stressed syllable in the second half. Easy!

Other heavily stressed syllables in the first half CAN alliterate too, and usually do. But the final heavily stressed syllable, as a rule, does NOT alliterate. This helps to signal that the line is ending, helping the audience to perceive the metre.

The first line of Piers Plowman is an exception, and therefore noteworthy:

Syllables that are not heavily stressed may also alliterate, but note that this is not part of the alliterative metre, and unlikely to be of great interest to audiences of alliterative verse. So in a line like 'and hadden leve to lyen al hire lif after' ('and had leave to lie their whole life after', Prologue l. 49), the verb hadden and the pronoun hire happen to alliterate with each other, but this is entirely coincidental to the metrically required alliteration of the heavily stressed syllables: 'and hadden leve to lyen | al hire lif after'.

There's a lot of debate about how many syllables poets thought they could get away with cramming between the heavily stressed ones, and different poets clearly had different policies about this. It doesn't help that most fourteenth-century alliterative poets were saying -e at the end of words, but by the fifteenth century people had given up on this vowel, so there is no question that the work of fourteenth-century poets like Langland and the Gawain-poet was being read and copied by people who spoke very differently, even within the poets' lifetimes. But basically, the a-verse could only have up to three stressed syllables (more usually two) and the b-verse could definitely only have two. You can only get so far into an English sentence before you get to a heavily stressed syllable, so this naturally limits how long a line can be!

Rather than worrying about what rules different poets were trying to follow, just keep an eye out for abnormally long lines. For example, when Langland is being classy and restrained, like at the beginning of Piers Plowman, he writes lines of about 13 syllables, with up to about three syllables in between the heavily stressed ones. (NB the following syllable counts assume that -e wasn't pronounced before a vowel).